Article 4 - Lignum Bowls

ARTICLE 4 - Lignum Bowls

(Originally published in 1996 and revised in 2009)

In this forth article, I thought a mention of the traditional

manufacturing methods might be of interest. Drakes Pride is

probably the last of the bowls manufacturers to still make "brand

new" Lignum Vitae bowls. These are made mainly for the crown green

bowls players (See photograph)., but occasionally also for a lawn

bowler, however at over £300 per set of four (1997 price), perhaps

they are only used as presentation sets.(Since 2002, based on World

Bowls Ltd. regulations we could not put the official stamp on

Lignum Vitae Bowls)

The colour and grain of high grade

Lignum Vitae Bowls, polished are a delight to see and as timber has

a warm 'feel' they are also very tactile.

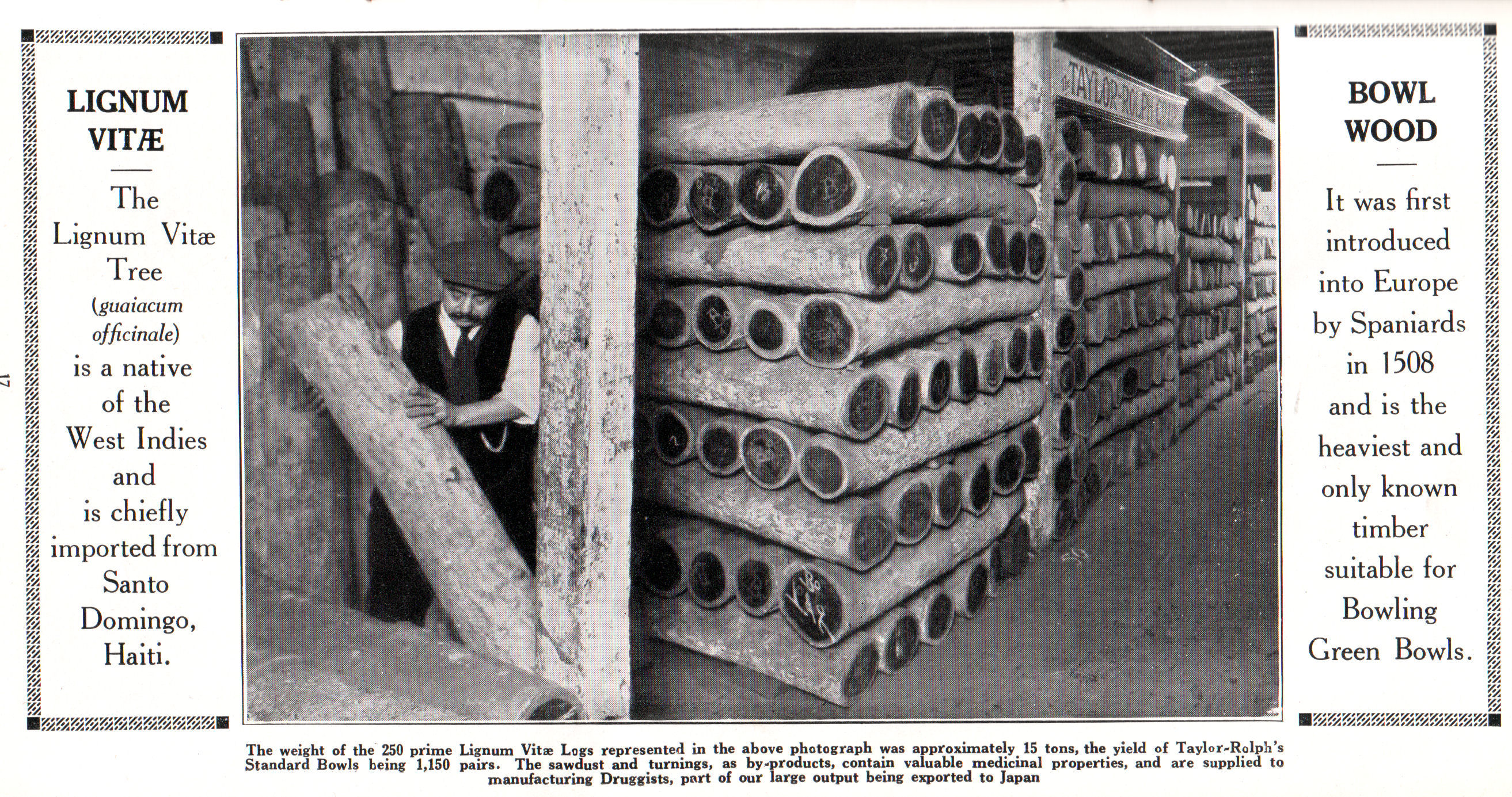

Picture from Taylor-Rolphs 1935

catalogue showing their stock of Lignum Vitae logs

Lignum Vitae is a timber now on the

United Nation CITES list, thus requires special licences for the

export and import of same, and so it is even more difficult to

obtain suitable timber for the manufacture of bowls.

Lignum Vitae is one of the most

outstanding of all timbers, it is not only one of the hardest and

heaviest known, but has an almost unique property of being

self-lubricating. As a result, not only was it used for lawn bowls

but also for bearings and bushing blocks for propeller shafts of

ships, as well as being ideal for pulleys on sailing ships. Those

who had high quality clothes mangles, to put your washing through,

would also perhaps have recognised that the bottom roller was also

made from Lignum Vitae. The Taylor-Rolph picture of logs mentions

its medicinal properties and they exported the turnings and saw

dust to Japan. The writer can also remember that the Lignum sawdust

was sold to a London pharmaceutical firm.

The tradition of making bowls in Liverpool goes back a long way.

It was in 1820 that Darlington's was founded and therefore as

Drakes Pride was formed from the nucleus of that firm, it can trace

its methods and knowledge back to that date. Of course Thomas

Taylor's of Glasgow, are older, they are celebrating their

bicentennial this year(1996), having been founded in 1796, but they

no longer produce Lignum Vitae bowls.

The way Lignum Vitae bowls were made was a very skilled job, not

just from the skills needed for hand turning, but right from the

initial selection of the original logs. The careful cutting to

ensure that a set of four came not only from the same log but from

along side each other in that log. In the 1970's it was already

getting difficult to obtain Lignum in log form as the exporting

countries wanted to retain some additional value in their country.

So Drakes Pride imported turned cylinders of lignum, the centre of

the cylinder being as close to the heart of the log as possible.

The cylinders were dipped in wax to seal them to prevent cracking

during shipping. The wax basically did the job of protecting the

cylinder of timber in the same way the sap wood would have done

when it was shipped in log form.

There are three species of Lignum Vitae and only one of which is

really suitable, that is "Guiacum Officinale", so knowledge of the

species is required. Interestingly, Lignum is bought by weight,

rather than the more usual, for logs, cubic measurement. Once the

logs were accepted as the correct species, the next stage in the

selection can proceed.

Those logs which had too large a heart crack, would be

unsuitable, note however that all Lignum Vitae has a heart crack,

and it is likely that the white mounts (discs as seen in the

photograph of a pair of bowls at the start of this article) were

used originally to hide these cracks. The heart of the timber has

to be so positioned, in the log to allow it to be the centre of the

bowl. So if it was too close to one side to allow for this, the log

would be rejected. The heart timber, itself, is very dark in

colour, but the sap wood is pale yellow in colour and is sharply

defined. It is only the dark timber that is required, so any logs

that did not have sufficient diameter of dark timber would be

rejected, and equally if the log was too large in diameter,

resulting in too much waste this would also be rejected. After the

initial careful inspection and selection, the timber passing the

selection could be purchased.

The next stage is to produce the "blanks" from which the

craftsman turner, would make the bowls. For any Lignum bowls, to

make a set the "blanks" they have to come, not only from the same

log but also side by side in that log. Otherwise, the specific

gravity of the bowls would not be the same, given that they are

from a naturally grown piece of timber, and the likelihood of the

bowls being of "similar" weights, could not be expected or

achieved.

The first stage of producing the "blank" from the selected log,

was basically to produce a cylinder which could be put between the

centres of a ball turning lathe. It in worth noting that at every

stage, the timber requires careful inspection and sealing, to

ensure that it does not crack.

The craftsman turner, would take the rough ball shaped blank,

and turn it into the recognisable shape of a bowl. The skill

required to do this, using only hand tools and a template, to give

the running sole shape, was to say the least an art, and was down

to eye and hand co-ordination as well as experience. By offering up

the sole template to the piece being turned, and judging the

amounts of material to be turned off, the craftsman would produce

the required shape and dimensions, they would also position the top

rings which delineated the running sole.

After that first stage the mounts (discs) would be fitted and

the inner rings and any other decoration would be cut onto the

bowl. Then followed the next, most skilful job, checking out the

bias. As you can imagine, even allowing for the skill of the

turner, the bowls required biasing to that specified by the

customer and or the governing bodies of the game. The examination

of the bias was, and still is, done on the test table, which is, as

mentioned in an earlier article, used as a quality control device

rather than the means of knowing what the bowl would do on the

green.

It is amazing, just how little material needs to be sanded off

to adjust the bias of the bowl either to make the bias stronger or

weaker. The skill is knowing how to remove as little as possible,

whilst still being able to retain the basic geometric "proven

template" shape. If the "proven template" shape in altered then the

bowls may be able to be made to run down the test table acceptably

but might not do so on the green - thus great skill and knowledge

is required.

Finally, the bowl would have been hand polished either black if

the original timber was not considered to be 100% or natural, using

a clear finish, if the timber was considered the very best. I am

sure there are still a lot of crown green bowlers who have found

memories of the "Extra Quality" bowls, which were polished natural

and had the Deluxe decoration on them. I know that if any bowler

has lost their bowls, they always seem to describe them as being of

that quality! Now we use a very hard wearing spray finish rather

than hand polishing with shellac.

These traditional skills still exist. Although now the "ball"

shape blank is turned on the same C.N.C. lathes as we use for our

Drakes Pride composition bowls, which means that they are more

accurately made to the required geometric shape, than could have

been achieved, by even the most skilled craftsman. All the other

skills remain the same, especially, when it comes to the biasing.

The new Lignum Vitae bowls will lose some 20gms - 46gms in weight

in the first year, after that, with care and attention, involving

bowls being re-polished at least biannually they should give many,

many years of service.

One of the reasons that Composition bowls were first introduced,

was that in hot weather, as experienced in the Southern Hemisphere,

Lignum Vitae bowls were prone to split, the Dunlop company being

one of the first companies to introduce a replacement material

using a rubber compound.

So, in Australia and New Zealand, bowlers will probably

only know Lignum Vitae bowls from their display cabinets, whereas

Drakes Pride based in the North of England means we see many

thousands of Crown Green Lignum Vitae bowls each year as they pass

through our factory for renovation and re-polishing.

So, "woods" are still going strong, but the composition bowls

are taking a larger and larger market share. In the next article, I

will cover the processes of the manufacture of Composition

bowls.

Some Information on Lignum Vitae the 'wood' used for bowls

LIGNUM VITAE

(Guiacum officinale L.

principally; also G. sanctum L. &

G. guatamalense Planch. Family - Zygophyllaceae.)

Other Names.

Guiacum wood. Bois de Gaiac (Fr.), Porkholz (Ger), Pokhout

(Dutch), Lignum Sanctum (P.R.).

General Description.

Lignum Vitae is one of the most outstanding of all timbers, as

it is not only one of the hardest and heaviest known woods, but

also has the almost unique property of being self-lubricating -

that is, of containing sufficient oil or resin to make it suitable

for bearings, etc., without either catching fire from friction, or

needing any oil.

The sapwood of G. officinale is narrow, pale yellow in colour

and sharply defined. Logs which have lain for a long time in the

forest may lack the sapwood altogether. In Bahama Lignum (G.

sanctum) the sapwood is very wide, sometimes 9 in. in a 10in. log.

Heartwood varies from olive green to brown or almost black, often

somewhat streaked; on exposure the colour darkens. Figure is

occasionally fond, due either to changes in colour or a fine

ripple, caused by the very interlocked grain. The wood is slightly

scented, but this is only noticeable when the wood is warmed or

rubbed. The texture is fine and uniform, and the wood has a

characteristically oiled feel. Its weight varies from 72 to 83lb. A

cu. Ft. (when seasoned to 15 per cent. moisture content), averaging

about 78lb.

Seasoning.

A somewhat refractory wood to season, needing considerable care

to avoid streaks.

Strength.

Extremely resistant to abrasive wear although somewhat brittle

under impact, very difficult to split radially, but comparatively

easy on a tangential plane. Extremely hard: the Forest Products

Research Laboratory state that it is three to four times as hard as

English oak.

Durability.

Extremely resistant to decay and insect attack: damage has,

however, occasionally been caused to logs by longhorn beetles. The

wood is acid resisting.

Working Qualities.

It is difficult to work with hand tools and hard to saw and

machine, tending to ride over cutters in planning and increased

loading to pressure bars is necessary. The cutting angle should not

exceed 15 degrees. It turns excellently and takes a high

polish.

Uses.

Its principal uses are for bearings and bushing blocks, for

propeller shaft of ships (where it is reported to last from three

to seven years). No wood has proved satisfactory as a substitute.

It is ideal for pulley sheaves (where it has been reported to last

for 50 years in good condition), dead eyes, caster wheels, etc.

It is also used for

"woods" in the game of bowls, and for turnery; bowls, etc.,

of this wood have been made since the early 17th century. It is

stated that it is replacing metal for bearings in roller mills, in

steel and tube works, as it is cheaper and has a longer life than

metal, and needs no lubrication.

It has been used for sleepers in Panama, but these were taken up

after 30 years (because too small for a new track) and used again

for dock work.

Notes concerning its use for Bowling Green Bowls based on Drakes

Pride experience:

1) The best Lignum for bowls was said to be from Santo Domingo

and should be from Guiacum Officinale.

2) Drakes Pride expect 'new' timber to have a specific gravity

of about 1.36 sg. Which would fall to about 1.32 after 1st season

playing bowls.

3) Even in the UK Bowls made from the timber will crack and

become useless if left in direct sunlight or if they become too

hot. So it proved to be basically unsuitable in hotter climates

such as Australia and South Africa.

4) Lignum bowls are still used quite extensively for Crown Green

Bowls.

© Peter Clare 2009 - © E.A. Clare & Son Ltd 2018. This

article can only be reproduced in part or whole with the permission

of E.A. Clare & Son Ltd.